Usually, the official records of secret services reveal little far less about those being observed than they do about the various fears of those doing the observing. These fears can be retraced in the minutiae of state security records: their narratives, vocabulary, abbreviations, punctuation and omissions. On the 12th of February in Cabaret Voltaire, as the writer and artist Gabriele Stötzer read from her Stasi records, and an opera singer voiced her Stasi-alleged offence with characteristic trill, the fear expressed in the language metamorphosed into shrill sounds.

The hostile basic attitude of the person in question, as well as her objectives of disseminating hostile ideas and affiliating herself with other similarly hostile persons as sympathisers, is apt to aid the achievement of the objective of the hostile political underground in the GDR.

In the original German, the mantra-like, almost incantatory repetition of the word ‘Feind’ – approximated here by the English ‘hostile’ – indicates not merely the hand of an agent handler in command of stylistically confident ‘Stasi-German’, it also hammers a particular word into these records, which itself first produces the ‘Feind’ (‘enemy’). In the case of Stötzer, the word ‘Feind’ refers not to a terrorist planting a bomb, but to a student hoping to improve rather than topple the GDR, and artist who mocked the established model of femininity in East Germany. The Stasi designated her a ‘feminist’, which at the time in the GDR was considered a Western import, and thus an ‘enemy’ word.

Gabriele Stötzer certainly does not draw a connection between the Stasi and Dada because of the immigration police’s monitoring of the 1916 Dadaists’ activities in Zurich. Back then, the Swiss secret service (the ‘political police’) recommended the expulsion of Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings from the country for the “propagation of revolutionary ideas”. Stötzer wants to, to quote Hans Arp, shift the attention away from herself and onto the “directors of stupidity”, and onto their reality-shaping verbal nonsense.

Stötzer is not however the only artist concerned with official records of herself. Only recently, Max Frisch’s painstaking close reading of state security records, Ignoranz als Staatsschutz? (Ignorance as National Security?), was published, courtesy of David Gugerli and Hannes Mangold. After his study, Frisch’s file, which the Swiss state security had compiled over the forty-two years between 1948 and 1990, was returned to him via due legal process. The largely ridiculous entries about meetings with intellectuals from the GDR have been meticulously corrected and ironically commented on by Frisch. Above all, he has supplemented them, and indeed with far more notable events than those the state security had taken note of once or twice a year, mostly through second-hand accounts. Frisch’s Stasi records, then, are presumably more ‘exact’ than the Swiss political police’s thirteen-page document.

The majority of artistic involvements with secret service records are found in Eastern Europe, however. For example, Cornelia Schleime, who left the GDR in 1984, re-enacted particularly banal sentences from her state security records photographically in her ‘Stasi Series’, such as those in which her “anti-social lifestyle” is criticised. To accompany these, she created a montage of frivolous, decadent self-portraits on fifteen different pages of the original record transcript: we see her slouched on a bed reading Bravo, dancing naked in a poppy-field, or posing in front of an American limousine. Schleime too visualises fears, namely those concealed behind the term “anti-social, anti-socialistic lifestyle”. The Hungarian artist György Galántai, on the other hand, made his state security files public via the internet, displaying them in his art archive artpool, in part also as a means of documenting performance art in Hungary. The first happening in Budapest had not been documented by anybody so accurately and in such detail as it had been by the national secret service…

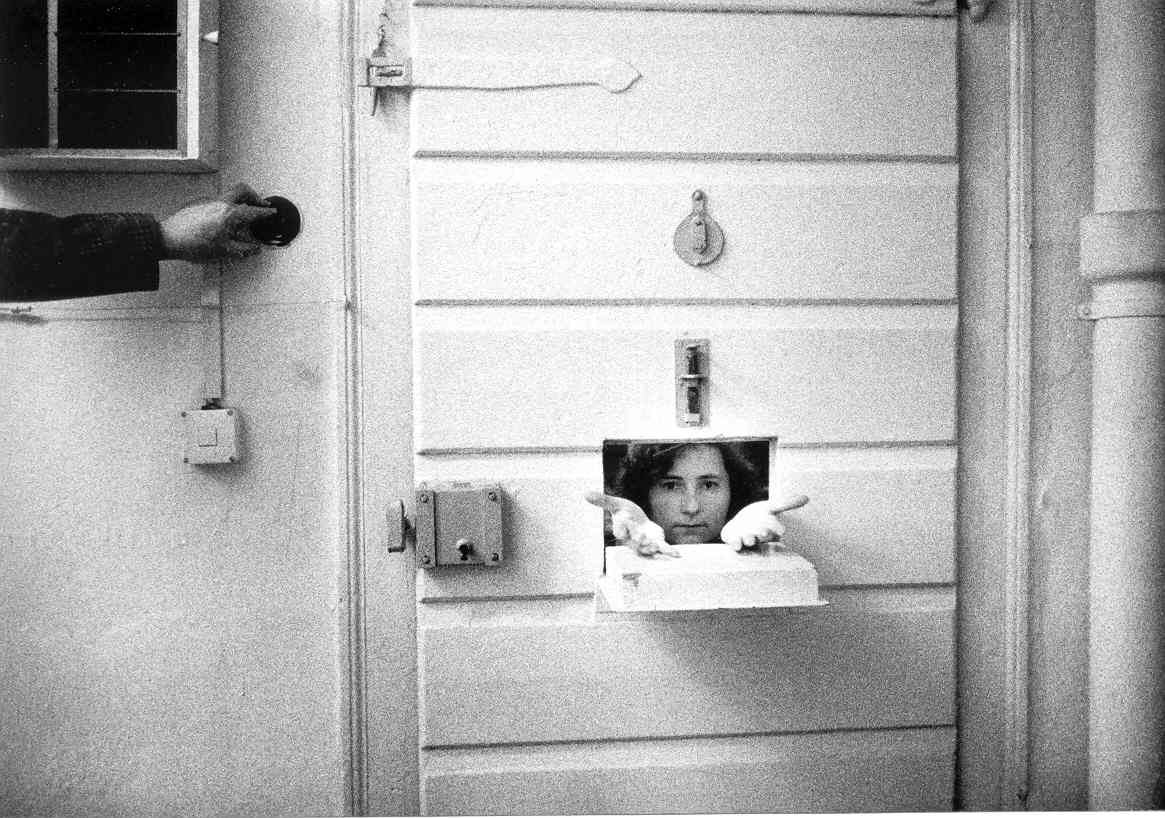

Back to Gabriele Stötzer, however. Reading her almost entirely preserved and voluminous records is not only important for understanding how authoritarian systems function; these records are also relevant from a literary-historical and art-historical perspective. That these documents can be read for the purposes of research is thanks to Stötzer herself. On December 4th, 1989, along with a group of other women, she occupied the Stasi headquarters in Erfurt, in order to seal the rooms and thus prevent the destruction of state security files. In Stötzer’s case, the documents in question number several thousand pages of “assessment reports” from agent handlers, surveillance reports from over twenty different unofficial collaborators, confiscated letters, surveillance photos, sketches of her apartment, her private ‘gallery in the hallway’ and reports monitoring her circle of friends. The catalyst for all this spying was a letter, also signed by eighty-three others, that she sent in 1976 to Margot Honecker, then the education minister of the GDR, as a protest against the expulsion from university of her fellow classmate Wilfried Linke. The consequence of this was her own expulsion, along with her being banned from attending university anywhere in the German Democratic Republic. After she took part in a signature campaign organised by well-known Berlin authors against the expatriation of Wolf Biermann in the same year, it was a step too far for the Stasi: Stötzer was, at the age of twenty-three, arrested and convicted to a year without parole in the notorious women’s prison, Hoheneck, in Stollberg, Saxony, for “defamation of the state”.

The files on Stötzer contain four “operative precedents” and give witness to the uninterrupted spying activity that took place between 1976 and 1989. The Stasi classified Stötzer during this period as a “person treated as operative”. The German equivalent of “treat” as used in this context, “bearbeiten”, describes in its connotative associations the true actions of the state security service. Monitoring and surveillance were always mere prerequisites to “treatment”. “Bearbeiten” – to “treat”, but also to “edit”, “revise”, “pester” and “bludgeon” – entailed, above all, “zersetzen” (“to degrade/undermine”) and “liquidieren” (“to eliminate”). With “zersetzen”, another key word of Stasi operations, Stasi functionaries denoted the “splintering”, “crippling” and “disorganisation and isolation” of opposing groups and individuals. According to Stasi guideline 1/76, this meant also the “systematic discrediting of public reputation, renown and prestige on the basis of related true, verifiable, discrediting information, as well as untrue, yet believable and irrefutable, and therefore equally discrediting information” (Lexicon of the Ministry of State Security).

The Stasi also instructed their unofficial collaborators (“IMs”) to invent facts as they saw fit. The IMs were given “cover stories”, with which to arrange the “systematic organisation of professional and societal failings in order to undermine confidence” (MSS Lexicon). Or one would “eliminate” artists’ galleries and other artistic actions, raising doubts about their capacity to successfully implement their planned activities (BSTU, AOP “Toxin”, 0011). In his book Stasi Konkret (Stasi Concrete), the historian Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk lists over two pages of further examples of established “Zersetzungspraktiken” (“undermining practices”) used against oppositionists, among them the spreading of rumours that they themselves are working with the Stasi!

In the case of Gabriele Stötzer, the Stasi’s “Zersetzungsarbeit” (“undermining efforts”) focused not just on her person, but also on her art. In their reports, all the unofficial collaborators always set the words “artistic” or “art” in inverted commas, and denigrated her literary texts as “uninteresting” and “unintelligible”. On top of that, the Stasi resolved “to create the preconditions for legal prosecution”. In other words, the state security attempted to imprison Stötzer for crimes they themselves had commissioned! The Stasi smuggled unofficial collaborators into Stötzer’s photo-actions as models. When Stötzer became interested during the shoot in cross-gender actions, the Stasi promptly sent in a transvestite. Mission: incite Stötzer to do a pornographic scene, which would then render her “criminally liable”. Stötzer claims that, when she showed the pictures semi-publicly the first time, an accusation of pornography was received, one which is not contained within the Stasi files and cannot be located anywhere else. When she wanted to make a Super-8 film with punks in Erfurt about the scaling of phallic architecture, the Stasi planted a particularly acrobatic punk in the scene, who then, in his role as a collaborator, became “Breaky”, the main actor in two films.

Those who depict the party dictatorships in Eastern Europe merely as societies under surveillance or control underestimate an essential political function of a national security service: its enactment mandate. It is therefore entirely correct, as historian Malte Rolf does, to depict such Eastern European party dictatorships as dictatorships of enactment. Admittedly, Rolf intended something else with this term: the permanent enacting of ideology in rituals and festivals. In this context, as the close reading of Stötzer’s state security files shows, “dictatorship of enactment” means the permanent enacting of events in the creation of internal enemies. There is much that remains to be done in a vast section of applied theatre, whose research – from a theatre studies perspective – is still somewhat fallow. With Gabriele Stötzer, the Stasi actively attempted to induce her to crime, and in other cases actively inhibited the artistic activities of the underground, so that censure, and thus a ban, would no longer be required, such as in cases where it was determined a gallery or an artistic action should simply be banned. The “elimination” of Gabriele Stötzer’s gallery was accomplished through the termination of her rental contract; in other cases, a broken water pipe would be arranged if an unofficial gallery opening was supposed to take place.

In Russia, we can even still observe these censure practices today. In December 2014, in teatr.doc, the most renowned off-theatre in Moscow, the showing of Igor Savychenko’s documentary, More Powerful Than Weapons, a film about the Maidan resistance and the war in east Ukraine, was cancelled due to a fake bomb threat. Shortly before the film began around twenty police officers, together with civil servants from the Ministry for Culture, burst into the cellar, evacuated the building, just about dismantled the screening equipment in the process, confiscated the film, ruined the premises and destroyed the cinema’s properties. The film screening could no longer take place.

While in current Russian cultural policy the practices of the secret services have obviously survived – perhaps a result of the secret service’s records being inaccessible – the now-defunct secret service archives of former Eastern Bloc nations, such as Hungary, Czech Republic and Poland are nowadays easily researched. This is not just bad news for the history writers of party dictatorships; it is also revelatory for the writing of literary and art histories. It may indeed be self-evident that one cannot simply use Stasi records as (art-)historical sources for those persons spied upon and their predecessors. One should never forget that the respective documents primarily illuminate the functioning of the Stasi itself. This also applies if, in Hungary for instance, the records fill particular gaps in the history of performance art: even here the records document not only a happening, but also the act of spying. Beyond this quasi-documentary value, it is nevertheless important to consider that the actions and values held by Stasi collaborators documented in these records were themselves reality-shaping. Collaborators also had the task of interfering in art production and impeding the work and recognition of specific artists. It is for this reason that, in today’s writing of art history, one should not be taken in by any of the Stasi co-produced canon.

by Sylva Sasse

German version: http://geschichtedergegenwart.ch/stasi-dada-gabriele-stoetzer-las-im-cabaret-voltaire-aus-ihren-akten/